Olde Paths &

Ancient Lndmrks

Christian Issues

Book Room

Tape Corner

Contact us

Checkout

|

|

||

|

Vol. 7,

No. 9

|

EDITED BY GLENN CONJURSKE

|

Sept., 1998

|

|

|

||

The Anatomy of a Rebellion

by Glenn Conjurske

And it came to pass after this, that Absalom prepared him chariots and

horses, and fifty men to run before him. And Absalom rose up early, and

stood beside the way of the gate: and it was so, that when any man that

had a controversy came to the king for judgment, then Absalom called unto

him, and said, Of what city art thou? And he said, Thy servant is of one

of the tribes of Israel. And Absalom said unto him, See, thy matters are

good and right; but there is no man deputed of the king to hear thee.

Absalom said moreover, Oh that I were made judge in the land, that every

man which hath any suit or cause might come unto me, and I would do him

justice! And it was so, that when any man came nigh to him to do him obeisance,

he put forth his hand, and took him, and kissed him. And on this manner

did Absalom to all Israel that came to the king for judgment: so Absalom

stole the hearts of the men of Israel. And it came to pass after forty

years, that Absalom said unto the king, I pray thee, let me go and pay

my vow, which I have vowed unto the LORD, in Hebron. For thy servant vowed

a vow while I abode at Geshur in Syria, saying, If the LORD shall bring

me again indeed to Jerusalem, then I will serve the LORD. And the king

said unto him, Go in peace. So he arose, and went to Hebron. But Absalom

sent spies throughout all the tribes of Israel, saying, As soon as ye

hear the sound of the trumpet, then ye shall say, Absalom reigneth in

Hebron. (II Samuel 15:1-10).

In the course of Absalom we see the method of rebellion, which varies

but little from one case to another. Rebellion is fomented by two means.

The first and most prominent of them is to breed discontent. The second,

which follows of course, or is present by implication, is for the author

of the rebellion to ingratiate himself in the minds and hearts of the

people, as the benefactor who will give them better things.

This is a sorry business, and those who engage in it are doing precisely

the work of the devil. This was exactly the method which the devil used

in the Garden of Eden. He first went to work to breed discontent, even

in Paradise itself, and then offered to give what God had withheld.

It must be understood that rebellion against authority is wrong. I realize

that there are deep and difficult questions involved in this, and I dare

not go so far as to say that rebellion against rightful authority can

never be justified. We know that disobedience is sometimes right. The

Hebrew midwives disobeyed Pharaoh, and were blessed of God for it. So

Moses' mother also. Daniel and the three Hebrew children disobeyed the

powers that were, and with the evident and miraculous sanction of God.

I have known of cases of wives disobeying their husbands, with the signal

blessing of God. But none of these are examples of rebellion. They are

instances of disobedience to a particular command from a rightful authority,

but not of a wholesale repudiation of that authority, or of a resistance

to that authority in general. Rebellion is the repudiation of the authority

of the powers that be, and if “there is no power but of God,”

it is certainly wrong to repudiate that authority.

But I understand that an abuse of authority naturally incites rebellion.

“Fathers,” the Bible says, “provoke not your children to

wrath.” (Eph. 6:4). Fathers are rightful authorities, who have their

authority from God, yet by an abuse of that authority they may provoke

their children to wrath, and that wrath will of course be directed against

the father, and invariably against his authority. The misconduct of those

who hold authority always weakens their authority in the eyes of the people.

An abuse of authority naturally incites rebellion, but still I cannot

see that God sanctions it. Just the contrary. He admonishes us to submit

even to those powers who abuse their authority. “Servants, be subject

to your masters with all fear; not only to the good and gentle, but also

to the froward.” (I Pet. 2:18). “Let every soul be subject unto

the higher powers,” says Paul, “for there is no power but of

God. The powers that be are ordained of God.” (Rom. 13:1). And this

though the only powers which Paul knew, whether Jew or Gentile, were ungodly,

and persecuted the church. When we hear modern professors of Christianity

claim that their rulers have forfeited their right to rule, because they

banish God from the classroom, or allow abortion, this is just pride and

self-will. These are sons of Zeruiah, who would take off King Saul's head,

while David refused to lift up his hand against “the Lord's anointed.”

The Roman government under which Paul wrote banished God from the earth,

and burnt and beheaded and crucified those who would bring him back, yet

Paul requires submission to that government, and calls it “a minister

of God to thee for good.” (Rom. 13:4).

Yet there may be cases of such extreme abuse of authority that God may

wink at the repudiation of that authority. I cannot prove that there is,

but I dare not say there is not. We may have a hint in that direction

in

I Corinthians 7:10-11, where we read, “And unto the married I command,

yet not I, but the Lord, Let not the wife depart from her husband. But

if she do depart, let her remain unmarried, or be reconciled to her husband.”

For a wife to depart from her husband is certainly to repudiate his authority.

Paul commands her not to do so, and yet immediately allows for an exception,

for what reason he does not say. I have long supposed that this may apply

to wives who are so abused that their situation is simply intolerable.

The same may be true when the subjects of a realm are so abused. God may

wink at their rebellion. I do not say he will, but I dare not say he will

not. God is not a tyrant, and in ordaining authority he never meant to

sanction tyranny.

It is safe to say, however, that most of the cases of rebellion in the

history of the world have little or nothing to do with any abuse of authority.

The widespread rebellion against parental authority in modern times, and

against all authority in general, does not stem from any abuse of that

authority, but rather from the passions of pride and self-will, which

are diligently instilled in men from their cradles, under the names of

freedom and democracy. No man is perfect, and there may be some faults

in both the character and the administration of every man who holds authority,

yet God knows that as well as we do, and still he ordains authorities,

and requires our submission to them.

Those who foment rebellion of course find something wrong with the authorities,

and it will be wonder enough if they do not find everything wrong with

them, and nothing right. If they can find no wrong, they will invent or

imagine some. If they can find any wrong, they will magnify it. If they

cannot magnify the facts, they will magnify the gravity of them, making

grave crimes of things which they are guilty of themselves, or which the

whole human race is guilty of, and so breed discontent, and of course

ingratitude, by hook or by crook.

This was the method of Absalom. “See,” said he, “thy matters

are good and right; but there is no man deputed of the king to hear thee.”

Whoever the man, and whatever his grievance, “the king” was

at fault in it. He had deputed no one to hear it. If this was a fault

in David's administration, it was a trivial one, but we are not so sure

that it was a fault. David's own door was yet open to those who had grievances,

and what need was there to depute anyone else? True, the man with a grievance

must go to Jerusalem to speak to the king, but this was not necessarily

evil. The multiplication of judges makes it too easy to sue. This leads

naturally to the multiplication of cases----the majority of them

either trivial or unrighteous----and this in turn multiplies strife

and discontent. “The Lord raised up judges,” we are told (Judges

2:16), but he raised up but one at a time. Of Deborah we read, “And

Deborah, a prophetess, the wife of Lapidoth, she judged Israel at that

time. And she dwelt under the palm tree of Deborah between Ramah and Bethel

in mount Ephraim: and the children of Israel came up to her for judgment.”

(Judges 4:4-5). This was of the Lord, and it was nothing different from

David's administration. We are not so sure, then, that the matter which

Absalom used to foment discontent and ingratitude in Israel was any fault

at all. If it was a fault, it was not a serious one.

But trivial or imagined faults will serve the purpose of the fomenters

of discontent and ingratitude as well as real and serious ones, for it

is a fact that it is very easy to breed discontent, especially discontent

with authorities. The sinful heart of man has a natural dislike for authority.

Those who stir the coals of discontent and fan the flames of ingratitude

always have the advantage, for those passions are too natural to the fallen

hearts of men. The agitators against authority use those passions to the

full. This is how labor unions operate. They find or imagine some abuse

in the authorities, and dwell upon that, artfully keeping out of sight,

meanwhile, all of the good in the employers, and all the good in the situation

of the laborers. They do not go to the management with their supposed

grievances, but preach them to all the employees, until they have turned

a shop full of happy workers into discontented agitators. By this means

one Absalom may turn the hearts of the whole nation. When I lived in Madison

twenty-five years ago, I worked in two different hospitals, first one,

and then the other. At the first there was a labor union----to

which I did not belong----and I found an undercurrent of discontent

pervading the place. Many of the workers were lazy besides. At the second

there was no union, and I found the employees in general hard workers,

and happy with their jobs. The difference between the two places was so

striking that I could not help but notice it immediately. No doubt the

spirit of discontent brought in the union at the first hospital, but it

was no doubt some union agitators who brought in the spirit of discontent.

Those who split churches operate upon exactly the same principle, and

the authority in the church is always the object of their attacks. The

fomenters of discontent know nothing of gratitude, but proceed after the

pattern of the devil himself, who kept all the goodness of God out of

sight, and said never a word to Eve of all the blessings of Paradise,

but spoke only of the one thing which he could discover which God had

withheld from her. The devil's followers in this evil business cannot

always be so bold, for the very goodness of a good man will act as a strong

barrier to their assaults. They must therefore tread gingerly, at least

at first, and praise the virtues of the good man very earnestly, only

to follow with, “BUT . . . , BUT . . . ,” he has this defect,

and that fault (however trivial), until at length the lean and ill-favored

kine have devoured up the fat and goodly ones, and all his goodness is

swallowed up by a few trivial faults. This is the work of the devil, yet

it is often done by pious Christians, who raise factions against the authorities

in the church. They do not go to the authorities with their grievances,

at least not until they have talked them about the church, and raised

a strong faction to support them.

But there are two sides to every question, and certainly two sides to

this one. It is a great evil to raise factions in the church against a

God-appointed authority, but we know too well that the places of leadership

in many churches are filled with men who are certainly not called of God----men

who are not apt to teach, whose children are not subject to them with

all gravity, who are greedy of filthy lucre, and who are not blameless,

sober, or vigilant, many of them novices and unspiritual besides. We can

hardly suppose it a virtue to continue such men in authority. Nevertheless,

it is a much greater evil to use the methods of Absalom to depose them.

An unqualified but true-hearted elder is a small evil compared to a fomenter

of discontent and discord. Far better to endure the misadministration

of an unqualified elder than to foment the spirit of rebellion, which

is founded in pride and self-will and envy, and issues in resentment and

slander and vengeance.

Whatever the authorities in the church may be, those who raise such passions

against them are doing the work of the devil. Such men cannot lead the

saints to green pastures and still waters. The real and only bond of union

in the factions which they create is opposition to the leadership. Such

a bond is much worse than worthless while it lasts, and it will not last

long after the leadership is deposed, or the faction departs for “greener

pastures.” I was once the object of such an attack myself, a strong

and of course passionate faction being raised against me, primarily by

the tongues of a couple of women. When this faction had gained strength,

their expressed intention was to put me out, and go forward without me.

Failing in that, the whole faction departed, but no two of them remained

long together.

No one in authority is without fault, yet when passions run high the most

trivial (or imaginary) faults are magnified into high crimes, and pursued

with a relentlessness which only evil passions can inspire. When such

passions reign, something will be found against the man in authority,

though the charges may be so frivolous as to be actually ridiculous. A

prominent Independent Baptist preacher was once bitterly opposed by his

church board because he bought a whole case of toilet tissue, to save

money, instead of buying one roll at a time. I heard this from his own

mouth. But the fact is, “the issue of the tissue,” as he called

it, was not the issue at all. The only real difficulty was the wrong passions

in his opposers. When I was the object of a similar attack a number of

years ago, one of the women who was prominent in opposing me, after bringing

many charges against me which were either false or frivolous, and failing

to convict me of anything beyond the trivial, at length settled upon “A

bishop must be blameless,” and relentlessly insisted upon the most

rigorous interpretation of “blameless,” as though it must mean

“perfect.” Her own husband, who was against me himself, sat

beside her, and by reason and Scripture refuted her interpretation of

that verse, but to no avail. She was not moved by reason, but passion.

Passion is the very essence of rebellion, and this is evil regardless

of the character of the authority. Whether David were angel or devil,

the spirit, manner, and course of Absalom was wholly evil, without so

much as one mitigating feature.

Observe, Absalom made it his business to speak to everyone concerning

this fault or supposed fault of David, and so bred discontent and ingratitude

throughout the land. If he had been an upright man, if he had cared one

whit for the good of the people, he would have spoken to David concerning

his supposed fault. But no. All the talk was about David, and none of

it to him. This is the method of all who foment discontent and ingratitude

and rebellion. It is the method of all who seek to undermine the authority

of pastors and elders in the church. If they speak to the pastor at all,

it will be after they have aired out their passions to the rest of the

people, and secured support for their position. When that is done, they

may go to their pastor with boldness, even with impudence, and claim the

agreement and support of such and such prominent persons in the church,

though if they did not capitalize upon the wrong kind of passions they

might have no support at all.

Observe also, none of these men came to Absalom with any grievance against

David. He went to them, to instill in their minds a grievance against

David which they had never imagined. In this he worked in the same manner

as the labor union agitators. Alas, so prone is the human heart to discontent

and ingratitude that the men of Israel never inquired after the character

of either David or his detractor, but allowed one of the worst men on

earth to carry them away in rebellion against one of the best.

Observe too that Absalom succeeded in corrupting the whole realm without

ever leaving his place at the king's gate. He spoke to all who had some

grievance, and turned the discontentment of their hearts against David.

Those thus corrupted would be sure to corrupt others, for men (to say

nothing of women) who are possessed by such passions will never hold their

tongues.

And while he thus turned the hearts of Israel against David, he stole

them for himself, with suave and smooth courtesy, and with flattery. With

a sinister cunning worthy of the devil himself, “it was so, that

when any man that had a controversy came to the king for judgment, then

Absalom ... said unto him, See, thy matters are good and right.”

Absalom, who had murdered his brother, Absalom, who had set Joab's field

on fire because Joab failed to respond to his call, Absalom, whose heart

was even now set against that good father to whom he owed all that he

had, Absalom was the last man on earth who had any business to speak of

“good and right.” He cared nothing about either good or right.

But he knew that such talk would take well with the people. When any man

came to the king for judgement, whether his cause were good or bad, whether

he were angel or devil, Absalom would fawn upon him with “See, thy

matters are good and right.” Men love to hear that their own matters

are “good and right,” and will naturally adhere to the man who

tells them so. But was every man in the right who came to David to complain

of his neighbor? Did the party which was in the wrong never come to seek

a judgement in his favor? Can it be supposed that a righteous judge would

have told every man that came to him that his own matters were “good

and right”? But Absalom cared nothing for “good and right,”

and could therefore flatter every man who came, and this had its effect.

In all this we see the usual method of those who labor to weaken or undermine

the influence of the authorities. The question of what is submerged in

the question of who. David's conduct was always wrong, and the matters

of every other man in Israel “good and right.” This was neither

reason nor righteousness, but only passion, and evil passion besides.

The American revolution is of course much glorified by the ungodly, and

the American church, more influenced by the intoxicating principles of

liberty and democracy than by the word of God, has generally regarded

it in the same light. But can the American revolution----can any

revolution----be justified from the Scriptures? The Bible says,

“There is no power but of God: the powers that be are ordained of

God. Whosoever therefore resisteth the power resisteth the ordinance of

God.” (Rom. 13:1-2). This seems plain enough. But every revolution

proceeds upon the principle that the powers that be are not of God. The

American revolution proceeded upon the principle that the existing authority

was not of God, and that resistance to that power was not only legitimate,

but righteous and godly. And why? “Taxation without representation”

was the ostensible issue, but what is the evil of that? As a plain matter

of practical fact, it would be difficult to say wherein their taxation

without representation was any worse than the taxation with representation

under which America groans today. It will of course be said that it is

“a matter of principle”----the most common meaning of

which is, a matter by which to justify belligerence and self-will. The

plain fact is, as “a matter of principle,” to resist the authority

for “taxation without representation” is in fact to resist the

existence of authority itself. It is to assert that authority must originate

with the populace, or operate only by the consent of the populace, or

within the limitations imposed by the populace. This is in fact to assert

that the governed have the right to govern the governor, which in essence

is to say that authority as such----authority which comes down

from God----has no right to exist. If every man were wise and righteous----if

every man were fit to govern himself and his governors too, as democracy

assumes and asserts----there would be no call for the existence

of authority. But the matter does not stand so. The fact that God has

ordained authorities indicates that every man is not competent to govern

himself, and it surely proves that every man does not have the right to

govern himself. “Foolish people,” says Francis Asbury, “will

think they have a right to govern themselves as they please; aye, and

satan will help them.” Was there ever an apter comment on American

democracy?

I know that there are deep and difficult questions here. We often see

the power which is ordained of God acting resolutely against God. Moreover----and

what man is more likely to feel----the power which is ordained

of God as a minister to the people for good is often seen to work directly

against the good of the people. The powers that be are often ungodly,

unscrupulous, and tyrannical. What then? The Roman power under which Paul

lived was ungodly and tyrannical, and yet Paul commanded submission to

it. He commanded submission to the power which crucified Christ, and imprisoned

and beheaded himself. Surely if there were ever occasion to breed discontent

with the authorities, it was in the time of the apostles, and yet all

that the apostles have to say on the subject is directly the reverse of

that.

It is most true that the saints of God, as well as the people in general,

often suffer under the regime of the powers that be, but does this give

them the right to repudiate them, to overturn them? The Bible says, No.

When the Lord stood before Pilate, “Then saith Pilate unto him, Speakest

thou not unto me? knowest thou not that I have power to crucify thee,

and have power to release thee? Jesus answered, Thou couldest have no

power at all against me, except it were given thee from above: therefore

he that delivered me unto thee hath the greater sin.” (John 19:10-11).

The power which Pilate had to put Christ to death, or to release him,

was given to him from above, and Christ submitted to that authority and

to that death, unrighteous as they both were.

The recourse of the saints is not in rebellion or revolution, but in faith

and patience. “If ye suffer for righteousness' sake, happy are ye.”

(I Pet. 3:14). David suffered for righteousness under Saul, yet so far

from resisting Saul's authority, he everywhere upheld it. When David stood

over Saul, while Saul slept, “Then said Abishai to David, God hath

delivered thine enemy into thine hand this day: now therefore let me smite

him, I pray thee, with the spear even to the earth at once, and I will

not smite him the second time. And David said to Abishai, Destroy him

not, for who can stretch forth his hand against the Lord's anointed, and

be guiltless? David said furthermore, As the Lord liveth, the Lord shall

smite him, or his day shall come to die; or he shall descend into battle,

and perish. The Lord forbid that I should stretch forth mine hand against

the Lord's anointed.” (I Sam. 26:8-11). David could speak thus precisely

because he had faith, and this is the proper recourse of the saints under

tyrannical rulers.

But observe, David spoke so also because he understood that Saul's authority

came from God. Absalom knew nothing of this, or cared nothing about it.

He could therefore repudiate God-ordained authority, and assume that authority

to himself, with the same complacency with which he put off his coat or

put on his shoes. “But Absalom sent spies throughout all the tribes

of Israel, saying, As soon as ye hear the sound of the trumpet, then ye

shall say, Absalom reigneth in Hebron.” And soon enough he was reigning

in Jerusalem, while David fled across Jordan. Absalom was on the throne,

and David removed from it, but the fact remained that David was “the

Lord's anointed,” and Absalom was nothing, though he was, for the

moment, the choice of the fickle multitude.

But there are deep and difficult questions here also. Israel was a theocracy.

There is no civil theocracy on the earth today. The secular powers are

ordained of God, but they are not anointed of the Lord. It must be otherwise

in the church, where those whom the Holy Ghost has made overseers are

certainly anointed of the Lord as well as ordained of God. To repudiate

such authority is as much to reject the Lord's anointed as Absalom did,

and those who do so no more become the Lord's anointed by their declaration

of independence than Absalom did. Yet in the secular realm, where none

can pretend to the anointing of the Lord, “the powers that be are

ordained of God,” and we suppose that if one overturns another, it

must be the authority which is in power which is ordained of God. It is

a fact that God has often used rebellions and revolutions to remove one

power, and establish another, and when that is done, the new power is

as much ordained of God as the old one. Yet the saints of God have no

business in the rebellion. It is none of their sphere. It is against faith

and against the plain command of God. And perhaps the worst of it is,

the spirit and method of rebellion are absolutely destructive of virtue

and spirituality. These tender plants cannot live in the atmosphere of

rebellion. This is true whether the rebellion is in the nation, the family,

or the church. To breed discontent, where men were contented before, is

a sorry business on any account, but to breed discontent where gratitude

and deference are called for is the very work of the devil.

But I must turn to another facet of the matter, which I hope has been

in the minds of my readers throughout this article. If “the powers

that be are ordained of God,” it would seem that the only necessary

qualification for the secular powers is that they are in office. If they

are in office, we have no right to resist them. Likewise of parental authority.

No child has the right to repudiate his parents' authority because he

does not approve of their ways----nor even because God does not

approve of their ways. It is far otherwise, however, in the church of

God. There are specific and stringent qualifications for elders in the

church, and no child of God has any call to submit to the authority of

those who fail to meet those qualifications. It is really an evil to be

content in such a situation. It is the fruit of lukewarmness. Ecclesiastical

tyranny is one of the greatest evils under the sun, and incompetence and

misadministration in church authorities is a great evil also. It is a

plain fact that there are many ecclesiastical authorities which have no

right to exist, and which ought to be either deposed or abandoned. But

where this must be done, it must be done in a Christian manner. No man

has any right to do evil that good may come, and no man therefore has

any right to set himself against the authorities in the church after the

manner of Absalom.

Yet it remains a fact that men will never move to do anything about such

situations unless they first become discontented there. Might it not be

the work of the Lord to make men discontented in an evil situation? Indeed,

is it not the very work of an evangelist to make the prodigal discontented

in the far country? It is certain he will never leave the far country

so long as he is contented there. To breed discontent, then, may be the

work of the Lord.

Whether among the godly or the ungodly, I cannot help but look upon it

as a hopeful sign when I see a man become discontented. But there is more

than one kind of discontent, and it is certain that most of the discontent

on the earth is evil. On two different occasions during the past couple

of years I have received phone calls from men obviously discontented with

the present state of the church. At first sight, this is hopeful. Only

the most ignorant or the most lukewarm could be contented with the church

as it is today. But as I listened to these men talk, I soon observed that

none of their discontent was with their own state. Both of them talked

incessantly, so that I could scarcely speak at all. This is a pretty certain

mark of pride. And the one word which was most prominent in the speech

of both of them was “they.” They do this----they won't

do that----they don't understand----they are ignorant----they

are worldly, etc. Such discontent is worse than worthless, and those who

talk so, and expect me to encourage or countenance them, are sure to be

disappointed.

It is true that the prodigal was discontented with his circumstances and

his surroundings, and this it was which first moved him with thoughts

of returning to his Father, but above all he condemned himself. He did

not arise and go to his Father, and say to him, “Father, they sent

me into the fields to feed swine, they took no notice of me in my want,

they had no compassion,” etc. No, but “Father, I have sinned

against heaven, and in thy sight, and am no more worthy to be called thy

son.” The evangelist who stirs up discontent in the heart of the

complacent sinner does well, so long as he leads him to blame himself

for his troubles. Rebels and revolutionaries never operate on this plan.

They rather set to work to stir the passions of the prodigal against his

employer, for the indignity put upon him in sending him into the fields

to feed swine (while the employer enjoyed the luxury of a fine house and

good food!), against the uncaring populace, which took no notice of his

need, against the rulers of the land, who allowed such evils, etc. There

is a vast difference between discontent with my circumstances, my sin,

and myself, and discontent with my circumstances and the authorities over

me. The rebellious in heart always labor to stir up the latter. This was

the way of Absalom. This is the essence and spirit of rebellion, and it

is always wrong, even where the authorities themselves are evil or unqualified.

It is wrong because its very essence consists of wrong passions and evil

deeds. Who can tell of a rebellion, a revolution, a church split, a repudiation

of civil, ecclesiastical, or parental authority, which proceeded upon

the principles of quiet humility and gentle love? In the church of God

such a thing may be, but rarely is.

But there is yet another facet of this subject of which I wish to speak.

How ought the powers that be to deal with those who labor to undermine

their authority? It commonly happens that the authority is the last to

know it when some disaffected person is at work to destroy his position

or authority. The rebellious generally work in secrecy, and do all their

talking behind the backs of the authorities. They know to whom they may

speak freely, to whom they must speak guardedly, and to whom they dare

not traduce the authority at all. Adonijah knew whom to invite to his

rebellious uprising. “But me,” says Nathan the prophet, “even

me thy servant, and Zadok the priest, and Benaiah the son of Jehoiada,

and thy servant Solomon, hath he not called.” (I Kings 1:26). David,

of course, knew nothing of it. Neither did David know anything of Absalom's

stealing the hearts of the men of Israel. But had he known it, what ought

he to have done? It could hardly have been right for him to stand idly

by and allow the sinister process to go forward, but what could he have

done to stop it? Remember, all that Absalom was doing at that point was

speaking, and we have all been indoctrinated concerning the “fundamental

right” of every human being to the “freedom of speech.”

But is this right?

Whatever may be said for the freedom of speech in the civil realm----and

I do not meddle with that----I believe it one of the greatest of

mistakes in the family or the church. Who can believe that a father ought

to stand idly by while one of his sons secretly works, by means of “free

speech,” to breed discontent in the family and undermine his father's

authority? Exactly what should be done in such a case I do not pretend

to say. I only affirm that such activity ought to be stopped, by whatever

means the case requires. Any father who would knowingly allow such talk

to continue is a fool. Likewise in the church of God. Any member of the

church who seeks to breed discontent, by speaking against the elders behind

their backs, ought to be put out of the church, immediately and peremptorily,

before he has opportunity to raise a faction. His course is both sinful

and destructive. There is no reason to allow it, and every reason to curb

it.

It will be said----especially by those who are guilty of such practices----that

this makes the elders untouchable. It puts them beyond reproof. I say,

it does no such thing. Absalom might have spoken to David at any time

concerning his supposed fault, but it was not his purpose to correct David,

but to dethrone him. In the church this may be necessary. Some elders

doubtless ought to be put out of their office----not necessarily

for any crime, but simply because they are unfit for the position, and

ought never to have taken such a place to begin with. But if this must

be done, it may be done without any of the sinister tactics or the evil

passions of rebellion.

To conclude, Absalom is one of the worst characters to stain the pages

of Holy Scripture. He is the embodiment of self-will, and of all the evil

spirit and tactics of rebellion. Yet he has followers enough, many of

whom delude themselves with the fancy that their cause and their ways

are righteous.

The Power of Satan: Supernatural or

Paranormal?

by Glenn Conjurske

My readers may wonder what has become of me, when they see such an advocate

of plain and common English using such a word as “paranormal,”

but the word is not mine. In taking up the July issue of Dave Hunt's Berean

Call, I find the following: “However, we both [Dave Hunt and André

Kole, a Campus Crusade magician] agree that Satan's power is not supernatural,

but that only God can do true miracles, which override the laws governing

the universe. Nevertheless, in my opinion, Satan has paranormal power

that cannot be explained by science or duplicated by stage magicians.

When Satan, as a spirit being (who is subject to God's laws governing

the spirit world), invades our physical dimension, he is able seemingly

to defy physical laws to which we are subject.”

Kole apparently holds that all the miracles performed by various sorts

of spiritualists are mere sleight of hand, and claims that he can duplicate

any of them. Hunt denies this, attributing to Satan a “paranormal”

power, which yet is not supernatural. But if this “paranormal”

power is not supernatural, then it is only sleight of hand on a larger

scale. When the magicians of Egypt cast down their rods, they became serpents.

No doubt any magician could do this by sleight of hand, merely substituting

a serpent for a rod. If this is what Satan did, it was merely sleight

of hand on a larger scale. He did not pull the serpents from the hats

or sleeves of the magicians, but carried them in the twinkling of an eye

from some other place, and whisked away the rods likewise. Such the devil

doubtless could do, yet the Bible says, in Exodus 7:12, “For they

cast down every man his rod, and they became serpents.” “They,”

their rods, “became” serpents. If this miracle was only “seeming,”

then is the language of Scripture only “seeming” also? The scripture

says the rods “became” serpents. If we may interpret this language

as only popular and seeming, we have in fact so far become modernists,

reading the language of Scripture with a mental reserve, and have no very

solid basis for any belief in miracles at all. On the very same principle

by which we here prove that the devil only seemed to do a miracle, another

man may prove that Christ only seemed to do his miracles. The rods became

serpents, seemingly, and the water became wine, seemingly. I do not of

course impute such thinking to Mr. Hunt. I only affirm that the same argument

which proves the one equally proves the other.

The fact is, the Bible everywhere uses the same language of Satanic or

demonic miracles as it uses for divine. The false Christs and false prophets

“show great signs and wonders.” (Matt. 24:24). The antichrist

comes with “all power and signs and lying wonders.” (II Thes.

2:9). Here “power” is plural, and is the same term----dunamiV----which

is used everywhere else for miracles. It is perfectly legitimate to translate

this “all miracles and signs and wonders,” and all three of

these terms are used to designate the miraculous. Must we read the passage

with mental reserve, “all seeming miracles and signs and wonders”?

The beast in Revelation 13 (verses 13 & 14) “doeth great wonders,

so that he maketh fire come down from heaven on the earth in the sight

of men, and deceiveth them that dwell on the earth by the means of those

miracles which he had power to do.” Are these only seeming miracles?

In contrasting the strength of Samson with that of the demon-possessed

man, Hunt says, “In contrast to Samson's supernatural strength through

the Holy Spirit (Jgs 13-16), this was paranormal strength due to 'an unclean

spirit' (Mk. 5:2).” This is a distinction without a difference. So

far as I can tell, “paranormal” is only an uncommon word for

the common “supernatural.” The source of the power, whether

of the Holy Spirit or an unclean spirit, is irrelevant if the nature of

the power is the same.

Perhaps Mr. Hunt is defining “supernatural” in too high a sense,

and “miracle” in too narrow a sense. If “supernatural”

must mean divine, to the exclusion of angelic, and if a “miracle”

must be an act of divine power, then of course the devil is incapable

of it, but if the devil does by his own spiritual power the same things

that God or angels do by their power, why are they not miracles? When

Elijah called down fire from heaven, this was a miracle. When the beast

calls down fire from heaven, and the Bible calls it a miracle, why are

we to believe that this is only a seeming miracle----merely transporting

the fire from elsewhere, or bringing together such elements as would cause

spontaneous combustion? And even if the devil can do only the latter,

why is not this a miracle? Does Mr. Hunt know certainly that the beast's

miracle differs in essence from that of Elijah? I have indeed long supposed

that many at least of the divine miracles merely make use of the laws

of nature, by divine or angelic power, which is beyond human ability.

Scripture affirms this, in some cases. “And Moses stretched out his

hand over the sea, and the Lord caused the sea to go back by a strong

east wind all that night, and made the sea dry land, and the waters were

divided.” (Ex. 14:21). All but the modernists hold this to be a miracle,

and if the devil can thus use the same powers of nature, why is that not

a miracle?

We know certainly that the devil can overcome the force of gravity----perhaps

merely by lifting things, as every one of us can do in our own limited

way. The devil certainly overcame the laws of gravity when he lifted the

physical body of Christ to the pinnacle of the temple. Could he not then

also, by an exercise of the very same power, cause a man to walk on the

water? And if so, wherein would this differ from the Lord's doing so?

Was it not a miracle when Christ walked on the water, and enabled Peter

to do so? Certainly the devil could cause the iron to swim, by the same

power by which he took Christ up to the pinnacle of the temple. Was it

then no miracle when Elisha caused the iron to swim? We fear that any

attempt to deprive the devil of miraculous power will in the end work

against the miracles of Christ, and of the prophets and apostles also,

though this is far from Mr. Hunt's intent. He grants that the devil can

remove what he can inflict (as Job's boils). When Christ then healed the

woman “whom Satan hath bound, lo, these eighteen years,” was

this no miracle? Hunt grants the devil could have done it.

We confess that we do not know so much about the devil's power as Mr.

Hunt does. That he does not have all the power which God has we know.

What his limitations are we know not. We object to Mr. Hunt's doctrine

on this subject for two reasons. It seems to open the door to the weakening

of the testimony of Scripture, and it is wise above what is written.

If Any Man Think that He Knoweth

by Glenn Conjurske

“And if any man think that he knoweth any thing, he knoweth nothing

yet as he ought to know.” (I Cor. 8:2). These are very strong words.

If we press them to the full extent of their meaning, we must conclude

that the only ones who know anything are those who think they don't. This

would not be far from the truth, for it is certain that the most ignorant

are most often the most sure of themselves, while those who know the most

are those who most feel their ignorance. Still, we may know the truth,

and know that we know it. Paul, the author of this text, certainly did.

Are we then to interpret this scripture by making a distinction between

knowing the truth, and only thinking we know it? I fear such a distinction

would be of little use practically, for those who think they know are

commonly just as sure as those who know. I had an old teacher at Bible

school who used often to say, “A lot of people know a lot of things

that aren't so.” This is undoubtedly the truth, and it is just such

folks that this scripture speaks of. It is no doubt true also that none

of us yet know anything as we ought to know it. We are all of us ignorant

enough, and dull and lethargic besides.

But I do not suppose it necessary to put an exact and technical meaning

upon this text in order to use it aright. I scarcely suppose that Paul

had any such exact meaning in mind when he wrote it. He had a moral purpose

in mind, and that moral purpose is obvious enough. He meant to reprove

that pride which thinks it knows better than it does. That pride, though

nothing new, is perhaps the most prominent characteristic of the modern

church. Every man thinks that he knows----thinks that he knows

better than his neighbors----thinks that he knows better than he

does. The right of private judgement has been carried far beyond its legitimate

bounds. The principles of liberty and democracy and independence have

puffed up the whole world with self-sufficiency, and with an imagined

competence which does not exist. Every man thinks therefore that he knows.

In a letter just received, a correspondent laments that this spirit pervades

the Christian “web-sites” on the so-called “internet.”

Every one thinks he knows. Every one is eager to teach, none eager to

learn. Every one has his own special doctrine or emphasis, which will

cure the ills of the church, whether it be hyperdispensationalism, fasting,

deeper life, head coverings, King James Only doctrines, Calvinism, foot

washing, or having babies. Everyone thinks he knows, and everyone is therefore

eager to teach, while they all alike remain ignorant of the deep things

of God, and incapable of leading the saints to green pastures and still

waters, or even to solid wisdom. Everyone has notions of his own, and

everyone thinks he knows better than his God-given teachers. This is characteristic

of modern Christianity, and it is perhaps the greatest hindrance in the

church to the progress of the truth.

Not long ago I received an envelope in the mail with the return address

stamped in the corner “All Bible Questions Answered.” “Name

your subject,” said a note inside. I told the man he must be at least

500 years old. I am only about fifty, and therefore don't know much. But

the plain fact is, none of us know much. I count the man wise who knows

what the questions are. None of us know much concerning the answers. I

told this man I can answer all Bible questions also, but the answer which

I must give to most of them is, “I don't know.” Just last night

I was asked, “Why was Christ baptized?” I said, “I don't

know”----though I can say a few things concerning what the

reason was not. John preached the baptism of repentance, but the Lord's

baptism was certainly not that. We know that Christ was baptized “to

fulfil all righteousness,” but what that means I do not venture to

say. A man who was present said he knew a man at work who could answer

the question. He said that Christ was baptized to show his humility. “Yes,”

said I, “you could probably find three hundred and three answers

of that nature, every man being right in his own eyes, and none of them

knowing much about the matter.” The man who knows all the answers

has no notion in the world of what the questions are.

But to those who suppose they can answer all Bible questions, I may propose

a few. You can give an answer, and likely a wrong one, concerning the

extent of the atonement or the meaning of baptizw, but in those matters

which most deeply concern your own walk with God, or your own usefulness

in the world, you likely know little enough. At any rate, here are a few

questions for you.

Can you distinguish between the operations of the soul and those of the

spirit? Do you understand the importance of the difference?

Do you know how to “be angry and sin not”?

Do you know the difference between contentment and lukewarmness?

Can you distinguish between zeal and rashness?

Do you know the difference between a catholic spirit and looseness of

principle? Do you know how to walk in a narrow path with a large heart?

Can you discriminate between prudence and compromise?

Can you please all men for their good without being a man-pleaser?

Can you distinguish between faithfulness and bigotry?

Can you draw the line between faith and presumption----between

trusting God and tempting him?

There are yet more important questions than these. Do you know your own

ignorance? Do you know how to “think soberly” of yourself?

Do you know when to speak, and when to be silent?

Do you know how to prevail in prayer?

Do you know how to weep? Can you make men's hearts burn?

Ah! but you know Hebrew roots and Greek syntax! Yes, and what is it worth

if your mind is devoid of depth, if your soul is puffed up and dried up,

if you talk much and weep little? “If any man think that he knoweth

any thing, he knoweth nothing yet as he ought to know.”

A Few Books I Would Like to See Written

by Glenn Conjurske

Of the making of books there is no end, and there is surely no end of

the making of unprofitable books. Meanwhile, many of those books which

ought to be written are never written at all. Men write the easy books,

which may be written without any depth of thought, or study, or understanding,

or experience, but they pass by those which would require real depth and

learning, such as are only to be acquired by wide reading, deep study,

extensive observation, long experience, and much meditation. It has long

been my desire to write a few books of this sort, but I fear that most

of these dreams will never come to pass, as time and life are too short,

money is too short, and I am too busy.

I will at least suggest a few titles, and it may be that these will at

any rate suggest some profitable lines of study.

The Decline and Fall of Methodism. Methodism was the most vigorous and

spiritual movement ever to exist among English Christians, and perhaps

in the world. A President of the United States once said that if America

ever became corrupt, it would be the Methodists' fault, for Methodism

had more influence than all the other churches combined. Methodism fell,

along with other denominations, to modernism, but it did not fall by modernism.

Modernism has no manner of influence with the spiritual, and those who

fall to modernism only prove that they were fallen already. Methodism

fell by worldliness, and worldliness came in through the failure of discipline----that

is, by the failure to enforce its own standards----coupled with

a very defective doctrinal understanding of what the world is. Methodism

fell, in other words, by means of the very same state of things which

now prevails in Fundamentalism. An illustration of all of this from the

history of Methodism might prove most profitable today for those who have

ears to hear. The qualifications for writing such a book are two: an understanding

of the issues, and an intimate acquaintance with Methodism. The latter

would require the reading of some scores of Methodist biographies and

histories. I have done much of this, and made many notes on my reading,

but it scarcely appears that I shall ever have time to complete the work

and write the book.

The Arminianism of C. H. Spurgeon. Spurgeon, as is well known, was a Calvinist,

but he was a very inconsistent one. He was often accused of Arminianism

by more consistent Calvinists. The fact is, he was Calvinistic in his

head, and Arminian in his heart, and when he had occasion to do so, he

could preach Arminianism as well as any. A compilation of his statements

in this vein, along with the statements of others about him, would be

a great boon to the church. Such a book might be as one-sided in content

as Iain Murray's The Forgotten Spurgeon, but it would tell the other side

of the story, and might be titled The Unknown Spurgeon. But who has time

to read everything by and about Spurgeon? And in this day, who knows the

difference between Calvinism and Arminianism?

Primeval Heathen Traditions. When civilization and Christianity invaded

the territory of uncivilized paganism, mostly in the nineteenth century,

many of the pagans were found to possess traditions of the creation and

fall of man, or of the flood. So remarkable are many of these traditions

for their preservation of primeval truth that we can only suppose they

must have been passed down through the centuries from the old patriarchs,

though usually with some corruption. Most of these traditions have doubtless

now been obliterated before the march of civilization, but many of them

are preserved in the books of the missionaries who first lived among these

peoples. Some may also be preserved in the books of secular adventurers

who preceded the missionaries. A collection of these traditions is a desideratum

for the church. The qualification to write such a book is the reading

of some scores of missionary books, and probably the works of some secular

adventurers and explorers also. This, and the ability to discriminate

between the actual primeval traditions of the heathen, and those which

were influenced by contacts with civilization.

Christian Love Stories. These love stories are scattered here and there

throughout the realm of Christian biography----at least the biographies

of a certain era, neither too ancient nor too modern. Most of the older

biographies neglect to tell us anything at all about the love and marriage

of their subjects. The loss is more than repaired by some of the modern

writers, who wear their hearts on their shirt sleeves. Such love stories

as may be found, however, in some of the older books, are most edifying,

and would prove most instructive to young people, in the ways of love,

and the ways of faith and patience. Here is truth better than fiction.

To do justice to such a theme a man must first read some hundreds of biographies.

The Theology of G. Campbell Morgan. Morgan claimed to be a Fundamentalist

in doctrine, while he held the spirit of Fundamentalism in abomination.

To this day he is held in high repute by many Fundamentalists, and this

I regard as one more sign of the low spiritual condition of Fundamentalism.

The fact is, though Morgan was not actually modernistic in doctrine, he

was liberal. What is worse, his theology is generally empty of anything

to profit the soul or feed the mind. He dwells in the realm of liberal

speculations and airy vagaries, and betrays everywhere a mind not formed

by the Bible. His place in the esteem of Fundamentalists is undeserved.

To write such a book a man must know the theology of the Bible and the

ways of God, and have time (and inclination) to read at least a selection

of the works of Morgan. I say “a selection,” for I judge that

would be quite sufficient. I seldom read anything by Morgan without being

impressed with its emptiness and its departure from the plain truth. His

teaching is obviously well thought out, and usually clever. He frequently

scorns the beaten path, and aims at something more profound, and this

may account for his popularity, for human pride is always drawn to anything

which has the appearance of superior wisdom.

Common Proverbs Illustrated. The real life of common proverbs is in their

use, and it often happens that a proverb which appears to be the merest

truism becomes very telling by a judicious or witty application of it.

There is also an amazing elasticity in the application of many proverbs,

so that a single proverb often takes on numerous diverse turns of meaning,

all of them quite fitting, and none of them forced in the least. For example,

that excellent proverb “The half is more than the whole” is

exceedingly multifarious in its applications. John Wesley refers it to

the portion of the Society which remained after the unworthy members were

purged out. I have seen it applied also to the wished-for abbreviated

discourses of long-winded speakers, and to the Revised Version which might

have been if the revisers had done less revising. A proverb like “Let

well enough alone” has innumerable applications, and it is one of

the highest points of wisdom to know what is well enough. No doubt there

is a similar elasticity in the proverbs of the Bible, as there is also

in Scriptural principles. Many of them are true, in other words, in more

ways than one. The qualification for writing such a book is to spend a

lifetime reading good books, and noting down the occurrences of common

proverbs. If I had begun this a quarter of a century ago, I might be able

to write this book, but then I was too hyperspiritual to brook the use

of a common proverb.

The Conditions of Salvation in History. The gospel preaching of the present

day is very largely antinomian, and a wide departure from what was preached

in sounder times. Repentance and works meet for repentance----the

forsaking of sin, and holiness of heart and life----these were

preached as the necessary conditions of salvation by all the great evangelists

and men of God in history, including Tyndale and Luther, Menno Simons,

Calvin and Knox, Flavel and Baxter, Whitefield and the Wesleys, Jonathan

Edwards, Finney, Moody, Torrey, Spurgeon, and Ryle. At the same time there

has always been an undercurrent of antinomianism in Protestantism, the

fruit of Luther's Calvinism and his doctrine of justification by faith

only. These antinomian tendencies have generally been resisted by the

prominent men of God, but at times, and in certain quarters, they have

been strong. In the present day they have largely triumphed, in the extreme

antinomianism of such men as John R. Rice and Zane Hodges. Such a book

as I have in mind would consist of little more than a compilation of the

statements of various men on this theme. To write this book a man must

understand the truth of the gospel, and know the writings of the prominent

men in the history of the church. Such a book might serve to open the

eyes of the present antinomian generation, when they see that what they

call heresy is the very message which was explicitly preached by virtually

all the great men of God in history, and eminently owned of God in the

conversion of sinners.

A History of the Revised Version. Such a history already exists----A

History of the Revised Version of the New Testament, by Samuel Hemphill----but

it is so scarce that it may as well not exist. It is a most excellent

book, too, and deserving of the highest praise, so far as it goes. It

ought by all means to be reprinted, yet it may not be altogether sufficient

for the present age. It fails to deal with several important issues, and

the author is not so conservative as we could wish. At any rate, what

I wish to see is a thorough illustration of the principles involved in

the revision----a delineation of the very conservative revision

which was at first proposed and agreed upon, and repeatedly promised in

the most unequivocal terms by the revisers, their refusal to produce a

tentative revision, the secrecy in which their work was carried on, the

systematic contempt on the part of certain of the revisers for the rules

under which they worked, the very liberal revision which they ultimately

produced, the gloating of Jews and modernists over its weakening of fundamental

doctrines, the lamentation of the conservative and orthodox over the same,

and the peremptory rejection of the version by the English people. The

entire history is a conflict between conservatism and liberalism, and

indeed between spirituality and intellectualism. Westcott, Hort, and Lightfoot

disliked the conservative plan of the proposed revision, and took their

places in the company of revisers with the predetermined and concerted

purpose to “seize the opportunity,” and force a liberal construction

upon the rules by decided action at the beginning. This plan was too successful.

Lightfoot's warm advocacy of a minute “faithfulness” at the

first meeting of the revisers made their rules thenceforth a dead letter,

and the liberalism of this triumvirate triumphed. A history of all of

this would be most instructive to the present age, in which liberalism

and intellectualism have prevailed, and which is possessed with the craze

for making new Bibles. I would not expect such a book to close the flood-gates

which the Revised Version opened, but it might at any rate instruct those

who have ears to hear, concerning the nature and the value of conservatism

in revising the Bible.

These are a few of the books which I would like to see written, but ah!

tempus fugit, the vapor of life slips away, and I am too busy. It is more

likely that I shall write the last mentioned than any of the others. I

have most of the necessary materials in hand, am of course in diligent

search of what I don't have, have read most of what I do have, and have

taken copious notes. As for the other themes, some magazine articles on

some of these may have to suffice.

Ancient Landmarks

by Glenn Conjurske

“Remove not the ancient landmark, which thy fathers have set.”

(Prov. 22:28).

God made the earth without landmarks. Whatever landmarks exist have been

placed by men. Our fathers have set them. Yet God forbids us to remove

them.

There are, of course no landmarks in the sea. The man at sea knows not

where he is. Everything is unsettled. We have no means by which to get

or keep our bearings, except only from the sky above us. When that is

invisible we know not where we are, so that the man who has lost his bearings

on the land is said to be “at sea” or “all at sea.”

Landmarks, then, are most useful things, and though they are not of divine

origin, yet they have divine sanction. We are forbidden to remove them,

and this in spite of the fact that many of them have been placed improperly.

In our own country the land is laid out in sections of one square mile.

There is a right angle at each corner. Each section line is straight,

and one mile long. This is so in principle and theory, but it is rarely

so in fact. Any man may convince himself of this by a glance at a county

map, which exhibits the section lines, or a plat book, which exhibits

the property lines. The following cut exhibits the actual section lines

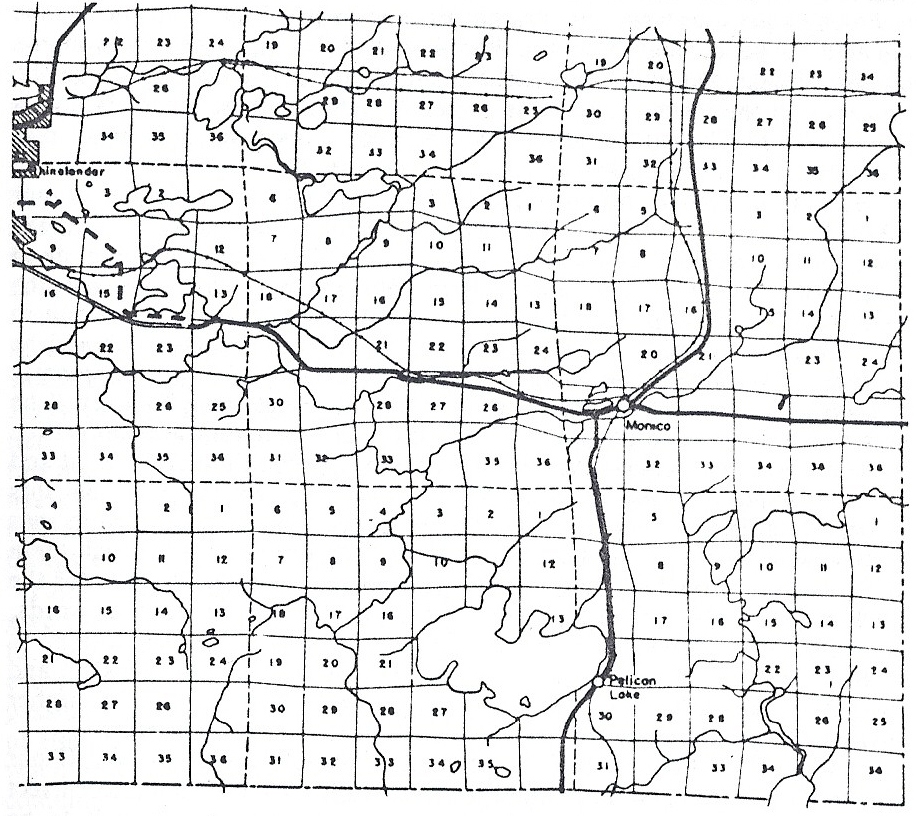

in the southeastern corner of the county in which I live.

Such the ancient landmarks are, whatever they ought to be, and yet God

forbids us to remove them. We would, however, expect every restless liberal

who views such a map immediately to raise the cry for revision. It is

inaccurate. It is wrong. It is full of errors. Our fathers doubtless did

the best they could with their limited knowledge and abilities, but they

were really incompetent blunderers after all. There is no reason in this

age of superior knowledge and advanced techniques to adhere to the mass

of blunders which our fathers made with their antiquated means. They did

as well as they could in their day, but their primitive means and equipment

were often baffled by swamps and woods and hills and lakes and streams,

and for all their labor and diligence, the sorry job which they did now

appears on every map in our hands. Our fathers themselves would have placed

the landmarks differently than they did, if they had had our superior

knowledge and equipment in their hands. To adhere now to the mistakes

which they made is only stubborn bigotry.

So speaks the liberal, but how speaks the Bible? “Remove not the ancient

landmark, which thy fathers have set.” “Thou shalt not remove thy neighbour's

landmark, which they of old time have set in thine inheritance.” God

does not concern himself with whether the landmarks were properly set.

He simply forbids us to remove them.

And why does God forbid this? He forbids it because it would do a great

deal more harm than good, if indeed it did any good at all. The gain in

having square corners and straight lines is so small that it is not for

one moment to be compared to the loss involved in upsetting every man's

property lines. Do you suppose that John Smith will much rejoice in the

accuracy of the “new” plat book, when he finds that his house is now

a part of old MacDonald's farm? Will widow Jones love the “new” plat

book, which has robbed her of her raspberry patch?

But “Doth God take care for oxen? Or saith he it altogether for our sakes?”

(I Cor. 9:9-10). Doth God take care for landmarks? As to the oxen, it

is certain that God does take care for oxen. On the word “altogether”

in the verse just quoted, Hodge says, “This is not the meaning here;

for this would make the apostle assert that the command in question had

exclusive reference to men. The word (ðÜíôùò)

should be rendered assuredly, as in Luke 4,43. Acts 18,21. 21,22, and

frequently elsewhere.”1 God takes care for oxen. “Should I not spare

Nineveh,” he says in the last verse of Jonah, “that great city, wherein

are more than sixscore thousand persons that cannot discern between their

right hand and their left hand, and also much cattle?” God takes care

for oxen, but this is not his primary concern. The purpose for which the

scripture was written was not merely to teach men to feed their oxen,

but to teach them to support the servants of the Lord, who labor to tread

out the corn for the flock of God. The spiritual purpose is the primary

one, or in other words, the application of this scripture takes precedence

over its interpretation.

So in the case before us. God concerns himself even with physical and

temporal landmarks, but these scriptures were written with a higher purpose

than that. The spiritual landmarks are his primary concern.

But what are the spiritual landmarks? Probably not doctrine. If our fathers

taught error, we are bound to teach truth. We are bound to correct every

scintilla of doctrinal error, so soon as ever we perceive it to be wrong.

The young, the proud, and the liberal commonly perceive that to be wrong

which is in fact right, but this is irrelevant. When a faithful and sober

man, taught of the Holy Ghost and Holy Scripture, perceives any part of

his doctrine to be wrong, he is bound to abandon it without delay, and

regardless of the cost, though it were taught by Darby and Baxter and

Luther and Augustine. We must be extremely careful, then, in any application

of the old landmarks to doctrine.

What then? I know of nothing to which the figure may be so appropriately

applied as the old and settled spiritual and theological language of the

church. Observe, we speak not of the land, but of the landmarks. The landmarks

may be of little significance in comparison with the land itself, but

they enable us to keep our bearings. They mark the divisions of the land.

The terminology may be insignificant in comparison to the doctrine, but

the terminology gives us the reference points by which we keep our bearings.

It gives stability, even to our thinking. When a man begins to substitute

new terms for old ones, he is doing what he has no business to do. He

is removing old landmarks, and the effect of this is always to unsettle

the minds of the people. We may surely rectify all that is erroneous in

a doctrine without renaming it.

And so far as we are able to tell, when men cast away old and settled

terminology, and replace it with new, it is generally their design to

unsettle the minds of the people. When the Jehovah's Witnesses struck

out the word “cross” from the Bible, and replaced it with “torture

stake”----when the modernists cast away “Jehovah” and replaced it with “Yahweh”----it was their design to unsettle the minds of the people.

It was their design to divorce the minds of the people from old and familiar

associations, and substitute new in their place. It was their design to

convict all our forefathers of incompetence and error, and replace both

our fathers and their religion with themselves and their own notions.

It may be that these liberals and cultists honestly supposed that their

new terms were “more accurate” than the old ones, but that is entirely

beside the point. It is not worth the weight of a feather. No man who

loves the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ either would or could contemplate

for one moment turning that cross into a “torture stake,” any more than

he could submit to the turning of “Jehovah” into “Yahweh.” Such an

operation gives such a wrench to all the most sacred feelings of the heart

that it is simply intolerable, upon any considerations whatsoever, to

any man who loves the things of God. If “torture stake” is “more accurate”

than “cross”----if “Yahweh” is “more accurate” than “Jehovah”----then “accuracy” must give place to something immeasurably more important.

It must give place to love, to devotion, to sacred ties, to heart feelings----in

short, to everything that is near and dear to loving and loyal hearts.

That modern passion for “accuracy” and technical correctness, which

values the dicta of Hebrew points more than the emotions of the soul,

is so petty a thing when standing next to the associations of the heart

that it is utterly contemptible. It is the passion of heads divorced from

hearts, which are the creation of unspiritual intellectualism, and not

of God. Observe now, I am not speaking of the substance of any fact or

principle or doctrine, but only of the terminology which is employed to

speak of it.

A review of the Revised Version (from the Standard, quoted in the Guardian)

says, “Where no material change in the sense or substance of the Authorised

Version has been shown to be required by the proper construction of the

original, the Revisers have, nevertheless, thought themselves justified

in mending the English and improving the grammar of passages which have

struck deep root in the hearts and memories of the English people. One

word has been substituted for another, at the whim of the New Testament

Company. Moods and tenses have been shifted about to satisfy some pedantic

scheme of syntactical symmetry. A sentence treasured up in the popular

mind, and enriched beyond description by the pathetic associations of

hundreds of years, has been tortured and crucified into precise grammatical

accord with the latest refinements of critical labour, upon the comparision

of early manuscript texts, and has thus been robbed of all its true value.

The system upon which the Revisers appear to have acted is, in our judgment,

altogether erroneous and deplorable. It is rash and reckless to shake

this noble growth of centuries [the attachment of the people to the Authorised

Version] by attempting to harmonise it with the correctness of self-opinionated

scholarship, or to regulate it by the doubtful standard of taste accepted

by a motley combination of theologians and professors. Their work of restoration,

with its standards of grammatical and linguistic exactitude, has disfigured

some of the noblest and best known passages in the English Bible. It has

introduced a jarring note in phrases associated with spiritual comfort,

intellectual emotion, and the strongest affections of the human heart.”2

This language is not a whit too strong. It affirms the undoubted fact

that when the old familiar language is cast aside, this gives a serious

jar to the heart, for which no grammatical exactitude can begin to compensate.

And what I wish to point out is that when new terms are substituted for

old, though it be with “no material change in sense or substance,” not

only is a serious jar given to the heart, but the mind is unsettled also.

This is so in every sphere. We who are accustomed to think in terms of

inches and feet and miles, pints and quarts, and Fahrenheit degrees, cannot

think with any efficiency in metric terms, and a generation of attempts

to coerce us to do so has left us just where we were. A trip is the same

length, whether we measure it in miles or kilometers, but all the associations

of our minds are in miles, and kilometers mean nothing to us. And if the

liberals can convert our heads from miles to kilometers, what then? Will

they re-survey the land also, or must we drive in kilometers through land

laid out in miles? The whole business is asinine, but not one whit more

so than the attempts to remove the old language from the Bible.

Rename a dozen or a score of the common elements, and this will unsettle

the mind of the chemist who has been long familiar with those elements.

The mind works with ease, with security, with comfort, and with efficiency

on familiar ground. All of this is sacrificed when old landmarks are removed.

This may have little effect on the young, who never knew the old landmarks,

or cared anything about them, and if there is one thing which is evident

in the new Bibles, which have removed so many of the old landmarks, it

is that these Bibles were not made for the saints of God. They were made

for the spiritually illiterate, for the young people, for the ungodly,

who knew little and cared less for their spiritual inheritance. Having

lost their hold upon their young people, and failed to awaken the interest

of the ungodly, the ill workmen quarrelled with their tools----blamed

the old Bible, and therefore made some dozens of new ones.

It may be that the young student of chemistry, just learning the table

of the elements, will suffer no inconvenience at all if half or all the

elements are renamed----no inconvenience, at any rate, until he begins

to consult the works of his predecessors. When he does that, he will find

that they speak a foreign language. He will find himself “all at sea,”

with no landmarks. And this is one of the greatest evils of removing the

old spiritual and theological language of the church. It breaks the ties

between the modern church and the old men of God. Remove “baptize” from

the Bible, and still it will live in the theological literature of five

centuries. If the landmark is misplaced, that may be unfortunate, but

it cannot be helped. To remove it now is to break the ties with all of

our fathers. That this is no concern of those who remove the old landmarks

is evident. The chemist who renames the elements proclaims by the very

act that he has little use for the works of his predecessors. Their work

is a mass of blunders. Their system is antiquated. We know better. Why

would anyone at this date wish to consult the works of our forefathers?

That this, in general, is the spirit of the makers of the new Bibles is

proclaimed by the nature of their work itself. If they esteemed and valued

their spiritual inheritance, they would at any rate spare the old landmarks.

God forbids their removal, not because they were perfectly set, but because

they are old, and our whole inheritance has grown up around them.

To take one illustration only from among scores of them, the old Bible

says, “But thou, when thou prayest, enter into thy closet, and when thou

hast shut thy door, pray to thy Father which is in secret; and thy Father

which seeth in secret shall reward thee openly.” (Matt. 6:6). The term “closet” will be found literally everywhere in the literature of the

English church----in every age and every denomination----and of course

the term is merely used, and not explained. What occasion could there

have been to explain what every child was familiar with? The closet is

the well known symbol for prayer and private devotion. We might indeed

fault the King James translators for abandoning “chamber,” which had

stood in the English Bible since William Tyndale, but it is four centuries

too late to undo that. The fact is, in the nearly four centuries which

have passed since the King James Version was published, the closet has

become the universally recognized symbol for prayer, in constant use in

all devotional and theological literature of every description. And must

we now have a generation of young people to whom all of these references

are unintelligible? They have never heard the term. They have been raised

on the new Bibles, which never use the term “closet” at all.

And this, as said, is but one example among scores of them. Our “inheritance”